In my previous article I argued that children must learn more than so called ‘technical’ skills to thrive in the digital world — that learning the arts, english, and history will give children a much better chance of success in life:

On Monday, I watched Sophie Winkleman speak passionately against the use of tech in schools at the ARC forum1 in London. I found myself giving a hearty yes and amen to many of her points, noting that she referred to much of the same research and stats as I have for Storygram. I’ll highlight her key points with some comments in a moment.

Before I do, a little about Our Soph (sorry, I should say Lady Frederick Windsor). You might recognise her as Susan from The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (2005), or Peep Show, or most recently the movie Wonka (2023).

Sophie is a patron of various charities and has become an activist and campaigner, speaking out against the overuse of technology in the classroom, as well as the effect of social media and smartphones on society in general.

Alright, let’s get into her message:

1. The paradox of digital connection

Sophie opened with a light-hearted story about watching two strangers sitting together on a London bus. Peeping over their shoulders, she observed them both scrolling through dating sites. The takeaway: while social media is supposed to connect people, in reality it isolates us from real-life connection.

“They were side by side, both seeking companionship or love, but they didn't even register each other's existence.”

Humans generally opt for minimal friction — if it’s a choice between an awkward conversation or simply swiping left, there’s no contest.

If you’ve been to an event in the past ten years you’ll have witnessed this phenomenon: crowds of people watching through their phones. It’s no longer possible to stand and watch fireworks or a concert without a sea of screens in front of you.

In this world, spontaneous human interaction does seem far less likely. Walking around London, I observe ‘z-mombies’ everywhere (zombies stumbling around while doing something on their mobile phones). Occasionally, I deliberately bump into them, just to make a point.

2. The digital destruction of childhood

For children, the impact of the digital age is even more dramatic. Speaking of her experience as royal patron of children’s charities, she described her amazement at the decline in the attitudes of the children she was visiting:

“The raucous exuberance of youth was being replaced with an anxious, irritable insularity, which was disturbing to see.”

I don’t think I was immune to this when I was growing up. I’m certain my parents witnessed some mild irritability when they told me to stop playing on my Game Boy. Technology was impacting children even in the dark ages of the pre-internet 1990s, but every decade the effect appears to ratchet up a notch.

3. The mental health crisis

Sophie then moved on to speak about the mental and physical effects of excess social media, drawing from statistics that I know well from The Anxious Generation (Jonathan Haidt) including:

“In the decade up to 2020, the suicide rate for younger teens increased by 167% among girls and 91% among boys.”

Are we simply numb to these statistics now? Or are we pessimistic about the efficacy of change? How can a statistic like this exist, out in the open, without society pressing pause on any possible cause?

Back in 2019, The Wall Street Journal released buried research by Instagram, that reported:

Instagram makes body-image issues worse for one in three teenage girls

Teenagers blame Instagram for increased levels of anxiety and depression

32% of teenage girls surveyed said when they felt bad about their bodies, Instagram made them feel worse

13% of UK teenagers and 6% of US users surveyed traced a desire to kill themselves to Instagram

There was a bit of hand-wringing at the time from Instagram when it emerged that they had buried these reports. But that was over 5 years ago. What has changed?

4. The hidden costs of EdTech

Sophie wants to take things further, though. She believes ‘EdTech’ doesn’t offer any real benefit to children, and argues for a return to the old, time-tested approach. She cites the example of Sweden:

“Sweden has taken note and been the first country to kick tech out of the classroom, reinvesting in books, paper, and pens. They had the courage to admit that EdTech was a failed experiment.”

Somehow, I can’t see this happening in the UK. The government are ‘all in’ on tech. AI is the future we are betting on. Kier isn’t going to risk turning his back on anything that looks like tech progress now.

TechUK ran a survey last year for parents in the tech sector or in tech roles to feedback their feelings about tech in schools:

When it comes to the use of technology in classrooms, 53% of parents and guardians believe teachers use technology moderately well in the classroom, compared to 19% who said it was used slightly well, and 15% who think they use it very well.

For the integration of technology into the wider curriculum, whilst 46% of respondents believed it was integrated moderately well, 26% thought it was integrated only slightly well, and 20% said it wasn’t well integrated at all.2

But note here that success here is defined by ‘how well’ technology has been integrated — not providing room for nuance, like should technology be integrated at all?

I will quote one further section of their findings which harks back to last week’s post:

Tech parents feel creativity will be key and we would encourage the reversal of the squeeze on creative subjects in the curriculum to restore art, design and music as core elements rather than ‘nice-to-haves’.

One of the words Sophie used frequently in her talk was ‘why’ — and as the evidence gathers to the impact of screens on children, it feels like now, more than ever, we have forgotten to use that simple word whenever technological advancement is being proposed.

5. Screen time stops play

Another argument that children of the 80s make frequently is that children need to get out and play. This has a whole section in The Anxious Generation titled ‘The decline of the play-based childhood’. Sophie says:

“A healthy childhood should involve lots of free fun—drawing, running, reading, writing stories, make-believe, kicking a football around, even just staring out of the window and wondering.”

I remember, fondly, all of the above from my childhood (even though I also remember, fondly, playing computer games).

Again, wider changes to the social fabric have surely had an impact here too. Back in the 80s, most parents weren’t thinking that their kids would probably be murdered if they let them go and play football in the park.

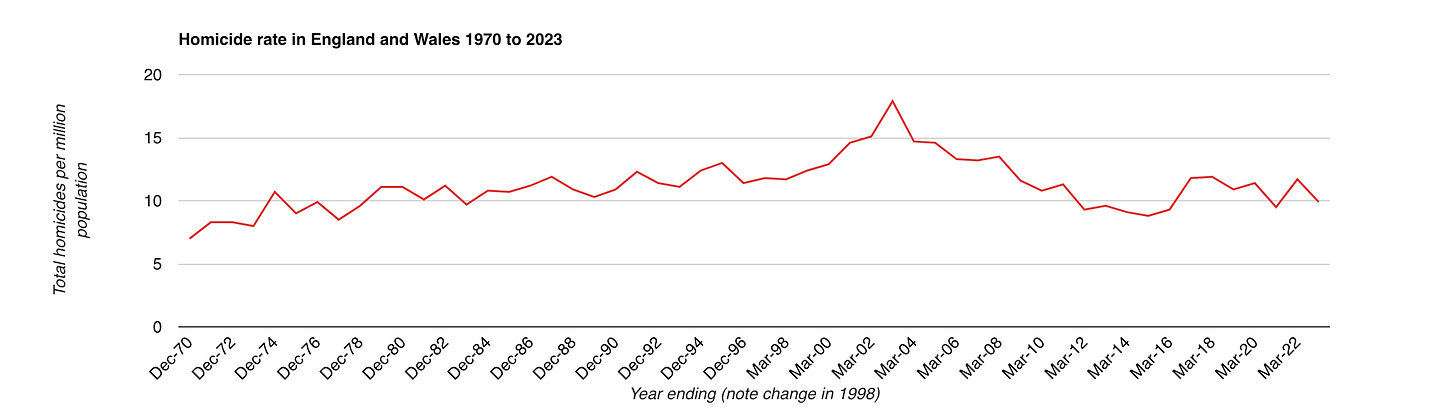

But we’ve lost the innocence and security of our free spaces — at least in our minds. In the graph below, you see the homicide rates in England and Wales from 1960 to 2023. (Morbid note: the spike in 2002/03 is attributed to Harold Shipman).

While there was a marked increase in homicides per million up to the beginning of the 2000s, a steady drop since then means we are no more likely to be murdered in the UK today than we were in the 1980s.

Do we feel safe? If not, why not? Maybe a bit off-topic for the Storygram Labs blog, but we can discuss this on the chat if you have an opinion:

6. A call to step up

Finally, Sophie made a call to both parents and government to take urgent action to curb the overuse of screens in children's lives.

“Rather than constantly having to prove that screen use is blighting childhood, we should ask simply: where is the evidence to prove that it’s safe?”

It feels as though the tide is turning against common acceptance of social media as acceptable for children/young teenagers. In industries that are known to cause harm, children are restricted from access; smoking, drinking, gambling — they all carry age limits. Furthermore, things that aren’t ‘great’ for adults, will often be far worse for children, hampering their mental, physical and emotional development.

Social media and screen use has had an easy ride until now, with limitations only imposed by especially strict parents (or countries, like China).

But around the world, governments are beginning to take notice. Australia is leading the way, banning children under 16 from social media last year. America still struggles to enact change, as the organisations behind these platforms have huge lobbying power. Much can be said about how the FAANG3 companies have skirted antitrust for the last few decades, but on that point I think we really are heading off-topic for this blog.

Closing thoughts

Many of Sophie’s ideas will be familiar to those who have read Jonathan Haidt’s book. The Anxious Generation provides a solid body of research that points to the damage caused by smartphones, social media, and the impact of the loss of free play, on children.

Humans have always preferred the route of minimal resistance.

Screens provide frankly miraculous ways for parents to stop their children from crying and to keep them entertained for hours on end, whether on long car journeys or while waiting in a queue. And so we took that route — of course we did.

Returning to a life of reduced tech for kids will add a lot of friction to our lives.

That’s why I agree with Sophie that there needs to be policy change to make reduced screen time feasible for the wider public, who will most likely continue down the easy route while it remains available to them.

But are we ready for that challenge?

You can watch the full talk here:

ARC, or the Alliance for Responsible Citizenship: “an international movement with a vision for a better world where empowered citizens take responsibility and work together to bring flourishing and prosperity to their families, communities, and nations.”

FAANG: Facebook (Meta), Amazon, Apple, Netflix, and Google (Alphabet)