I clearly remember the moment I was told that I wouldn’t be able to work in computers after school.

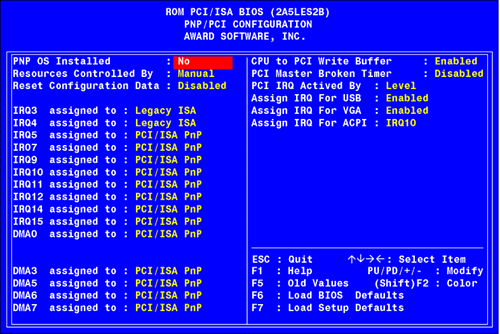

Ever since dad came home with that beautiful machine, the Intel 486, I had become obsessed. I learned to play in the command line, to dabble with the BIOS settings, and discovered a magical world of possibility when I unscrewed the back and peeled the shell off to reveal the glorious motherboard. Just thinking about it makes the hairs stand up on my neck.

Over time, mostly in my enthusiasm to get the maximum performance out of the machine, I found increasingly creative ways to break said PC. Sometimes, if I had been particularly creative, dad would have to call out our local computer fixer (who seemed like a bearded sage, but was probably only 25).

I loved these visits. While there was inevitably a sense of guilt at the fact that I was costing dad each time, I took the opportunity to glean everything I could from the poor guy. As he sat trying to unravel my marvellous work, I would question him over and over, hungry for knowledge. This was effective because over time I learnt to fix the computers that I broke myself (though I never stopped breaking them).

Over the years, I progressed from upgrading the RAM to buying new motherboards and processors, and installing fresh copies of Windows 95 (honestly, it doesn’t come much better than that). Much later, I discovered the Apple Mac, and began a whole new adventure of discovery (and computer breakage).

Against this backdrop, a noteworthy fact is that I was mediocre at maths. Not terrible, not great. Sporadically, I got the right answers, but often I wasn’t sure how. My dad was great at maths, but not all of us siblings seemed to carry that gene…11

I found myself in the second set (of three). This had life-altering effects when it came to my GCSEs, as in the second set you could only achieve a maximum of a B grade at GCSE. At the end of year ten (at 14 years old) my maximum GCSE grade had already been decided for me, even if I scored 100% on every exam. Not exactly motivating.

Worse, my careers advisor was aware of my inevitable impending sub-A maths grade. She sucked her teeth and drew in her breath, as she readied herself to deliver the shattering news. Because, of course, maths is the language of computers — everyone knows that. It’s obvious; if you can’t speak the language of computers with fluency, how could you expect to have a career in computers?

I understand the logic. PCs speak in zeroes and ones, at least until quantum computing really kicks in. Coding, especially back in the day, was quite close to machine code, basically meaning coders had to understand pretty well how to speak ‘computer’, which is not all that similar to speaking ‘human’. (Over time, programming languages have increased in abstraction, meaning they are easier to read and write (for humans) and more intuitive, but when I was 15 it was programming in C++.

To imply that maths is the only key skill required by someone ‘working in computers’ is farcical, nowadays. Everyone uses computers now, from farmers to pharmacists. Digital technology is the de facto way of working, of doing practically everything in modern life.

I won’t labour this point, but following school and university (where I didn’t do a computer science degree), I’ve spent 15 years working E-N-T-I-R-E-L-Y in computers, from running an IT company to heading up a team of web developers, to Chief Technology Officer at a national TV channel.

My point is: the careers advisor was wrong. So wrong, in fact, that I don’t think she had a clue what she was talking about. How great is that for someone whose job is to show young people their possible routes forward in life?

Today, there’s an obsession with making kids ‘digitally literate’. They must be trained in computers, to become used to using them for everything. If they are not digitally literate, they will fall behind, and be severely disadvantaged in the modern world.

I’m naturally a technophile, and I understand the benefits. For example, with homework, digital platforms can give students realtime feedback on homework submissions, enabling students to learn from their mistakes and grow, all while reducing the burden on the teacher.

However, the fact that many schools allow children to have phones completely boggles my mind. I managed to daydream quite effectively without the aid of the mini distraction box. If I’d had Instagram or WhatsApp, I’d be lost. Let’s face it, the Dopamine Cartel is more interested in growing ad revenue and keeping shareholders happy than worrying about children’s educational prospects.

I hear the cry coming up, ‘children must become digitally and tech literate’. But I wonder if schools truly understand what being digitally literate means, and how it will play out in the workplace of the future.

Here’s what BBC Bitesize says about digital literacy:

Finding information, sorting through information to identify the most relevant elements, evaluating reliability, citing sources, creating original content without plagiarising… these are all skills that can be learned (and probably learned more effectively) without a computer.

Here’s the crux: I was told I couldn’t work in computers if I didn’t have grade A maths. Now students are told they won’t be digitally literate without using computers — a desire for students to become digitally literate is important, essential, but the skills students need are more likely to be found in learning to read, assimilate, critique, spend time in thought, and writing (without internet access). After all, it’s much harder to plagiarise without copy and paste. The simple barrier of writing out by hand something that someone else wrote is enough to put some students off.

And children realistically don’t need much help learning how to use computers now, apart from specific tasks like citing or knowing which websites to download materials from: they are digital natives.

Software has consistently become more straightforward over the past several decades. Most software adheres to norms that have become established, whether language (such as, ‘save as’) or shortcuts (ctrl+c/cmd-c to begin plagiarism, ahem, I mean copy and paste).

These are standards which have developed and settled over time, which most of us are thankful for. Apps, too, have standardisation; developers who submit apps to the Apple App Store are tested against ‘user experience’ (UX) criteria, and forced to make changes if the app is deemed to break their UX rules.

It’s still possible to look back at some of the early relics of the web that are kept online for posterity (my favourite is the Space Jam site from 1996). In that era, the wild wild west of web design, sites were charming and full of character, but also a bit nuts. You have to hunt around for links and to figure out how to interact with the page. But standardisation has also made its mark on websites as the digital landscape matured. Frameworks like Bootstrap arrived, which standardise menus and grid layouts for web developers so they can more quickly make sites — but they also make life easier for users because more sites look and act in a predictable manner.

Millions of sites are now built with the Bootstrap framework, and once you have used one, you’ll know how to use them all. Personally, I feel the web is a duller place for it, though there are still exciting examples of websites around. My argument is simply this; digital tools (by which I primarily mean software and the internet) have become predictable and simple to use. When we marvel at a 2-year-old who can unlock an iPad, it’s (mostly) a marvel of one of the most intuitive software designs ever created.

Becoming tech or digitally literate in the sense of knowing how to use computers has never been easier.

The hidden settings that I used to play with (and break) have long been locked away from today’s playful hands. Most users need never see a command-line prompt, or adjust their BIOS settings (and I pity them for it). Equally, hardware is now practically inaccessible — Apple locks their devices with non-standard screws so they are difficult to open at home. RAM is often soldered in, so you can’t make your own upgrades (without buying a new computer).

The trend of simplification will continue. When AI really kicks in, it will replace many of the interfaces we are used to. But that need not cause concern — instead we will use simple gestures or phrases that remove the necessity for human to computer ‘translation’ at all, an ever higher level of abstraction.

In a STEM obsessed world, we are tempted to treat people like biological computers or machines. We seek every data point to gauge performance and maximise experience. Our schools are ranked and rated, with students under pressure to get the best grades from an ever-earlier age. Teachers are pressured by parents, and organisations like Ofsted to squeeze the best results out of the children.

At the same time, the arts and humanities have been decimated. We might blame government cuts, but the truth is the world doesn’t respect these disciplines anymore, in part because they are subjective, messy topics that don’t neatly fit into performance checkboxes.

Instead of pushing young people on to dead-end courses that give them nothing but a mountain of debt, we need universities and colleges to work together to address the gaps in our labour market, and create the valuable and technical courses our society needs.

The above is a quote from Gavin Williamson in 2021, then Education Secretary, speaking at the launch of the Office for Students' review of digital teaching in higher education.

The man responsible for ensuring students are well prepared for the digital world implies that arts and humanities are ‘dead-end courses’ that don’t provide value. In his estimation, only technical courses do.

Just as my careers advisor (gawd bless her) thought that maths skills were the only way to work with computers, so I see her thinking is symptomatic of a wider trend: an assumption that to use digital, means you must speak the language of computers. This is less the case than it has ever been.

As I write this (February 2025) it is now possible for me to have AI create a website or app for me that would take developers months to build. I don’t need to know or understand code. Likewise, using a simple written prompt I can create a cinematic, Hollywood-quality film scene, no production skills required. We’ve only just begun, and advancements will only accelerate.

I am not arguing that we don’t need skilled mathematicians, scientists, engineers, or doctors. More than ever, we require researchers and practitioners in these fields to solve problems for humans and to ensure the increasing digitisation of real-world problems serves humans and has an ethical basis (something which computers may vary on even more than we currently do).

But if we fail to bring up the next generation to understand history, read widely, think critically, appreciate the arts, paint, dance, tell stories — a generation lacking in all of this will lack hope and purpose, and may begin to believe the lie that they, too, are machines to be optimised and sanitised.

Art, history, literature; these disciplines serve to hold a mirror up to ourselves. They seek to express the inexpressible, to teach us to reach towards the unfathomable.

In the new digital landscape, workers will need to make wise decisions, to reason, write, and think. We’ll be faced with misinformation and ethical conundrums. It will be our choices, our ability to communicate our thoughts, that will help us succeed in that new world.

Bill Gates writes:

Many of the problems caused by AI have a historical precedent. For example, it will have a big impact on education, but so did handheld calculators a few decades ago and, more recently, allowing computers in the classroom. We can learn from what’s worked in the past.

Sure, Bill — thanks to calculators, we no longer need to be capable of mental arithmetic. With AI, we will no longer need to do mental… anything.

Digital literacy comes ever easier to digital natives. It’s the rest that we need to worry about.

Thanks for reading, and please let me know your thoughts and perspectives in the comments. Sharing is caring, so why not forward this to someone who might be interested?

Until next week!

Graham

PS I was reviewing my draft for this post when I read this annoyingly great piece from

and on . It’s so good it nearly put me off publishing my article.Here’s a quote which nicely encapsulates the idea that preparation for life (including digital life) is broader than we think:

… amidst all this hubbub of making sure our kids keep up with the technological tsunami, we forget to teach them “reality literacy”, the most fundamental language of all. It is well known that there is a critical window for language learning during childhood. If children are not exposed to language during this period of time, they will never acquire the capacity to speak. In a similar way we would suggest that there is a “critical reality window”, during which children and youth need deep immersion in the real stuff of life. Not just the linguistic, but the social, emotional, physical, everything.

While myself and at least one of my sisters struggled with maths, the others seemed fine, and my nephew now does calculus challenges with the same alacrity that I used to experience while playing Tetris.